|

|

Burntisland Oil Works

Site navigation - please use menu on left (click here to display it if not visible). If problems, use site map.

|

Burntisland Oil Works Site navigation - please use menu on left (click here to display it if not visible). If problems, use site map. |

Today, as you pass alongside the golf course on the way to Kinghorn Loch, it is very difficult to envisage the vast industrial undertaking which for a relatively short period - 16 years - dominated the area on the other side of the road. This was the Burntisland (originally Binnend) Oil Works which, at its peak, gave employment to almost a thousand men.

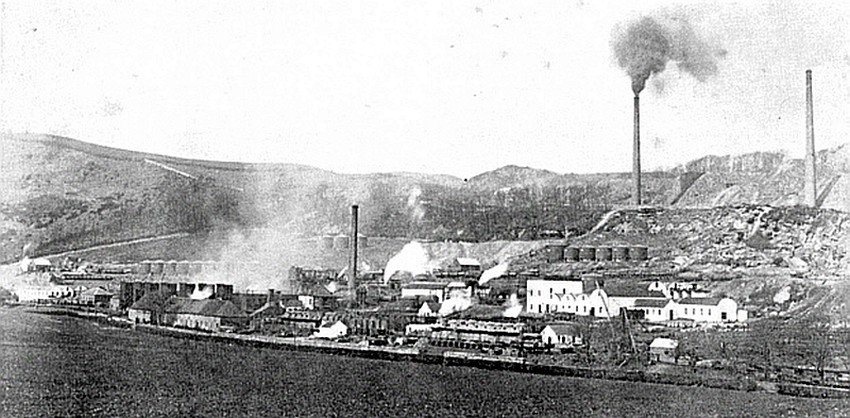

The Burntisland oil works in

production, probably around 1890.

Some remains can still be seen, close to the main road.

In 1850, James 'Paraffin' Young had launched the West Lothian shale mining and processing industry. When his patent expired in 1864, there were plenty of budding entrepreneurs ready to accept the opportunity presented. Small shale mining operations sprang up in various locations, several of which were in Fife.

The Burntisland Oil Works were established in 1878 to mine and process the shale deposits in the lower reaches of the east Binn. These deposits formed the northern extremity of a shale bed stretching for 22 miles from Cobbinshaw in the Lothians.

The man behind this venture was George Simpson, a coalmaster from Edinburgh, with the other directors coming from Glasgow, West Calder and Pittenweem. For the first three years, the operation was on a fairly small scale. By 1881, there were only 36 employees. Some of these lived in the old Binnend Farm buildings, a few at Craigkelly and Newbigging, and most of the rest in Burntisland.

In 1881, however, the oil works were bought by a new company headed by John Waddell of Edinburgh. Rapid expansion followed. The mine workings themselves eventually reached 365 feet below sea level at their lowest point. The average daily output of shale was 500 tons, which yielded 15,000 gallons of crude oil.

The crude oil was refined on site, and the main products were burning and lubricating oils, paraffin candles, paraffin wax, and sulphate of ammonia for fertiliser.

1887 brought further developments, when a branch railway line from Kinghorn Station to Binnend was opened and a new candle works was completed. The candle works buildings still survive, and are those on the south side of the road at Kinghorn Tannery. The new branch line ran alongside, and served the candle works as well.

William Erskine described the sight during the hours of darkness: "The blaze of light that emanated from the works at night illumined not only the surrounding district but formed a beacon to indicate to mariners their whereabout in the Forth."

The map shows Burntisland Oil Works when fully developed. The locations of both the High Binn and the Low Binn are marked (see also 'The Village at Binnend). The railway spur running south on the right of the map served the No. 4 pit at Grangehill.

|

The Kirkton Burn There are quite a few parallels between the Binnend story and the more recent Alcan story, not the least of which is that in both cases Binnend has been the recipient of the waste material. However, the question of getting rid of this material was less of a problem with the shale operation - it was simply dumped in ever-growing bings beside the mines. Those who have followed the recent saga of "Alcan's yellow pipe in the Kirkton Burn" will be interested to learn of an earlier pollution problem in that burn. In 1880, Robert Kirke, plantation owner in Suriname and Laird of Greenmount, obtained a court order to halt production at Binnend. The reason? - that the burn was being contaminated with the residual oil from the works. The employees and the local traders were enraged, and organised a march from Binnend to the town centre, where an effigy of the Laird of Greenmount was burned. The issue was resolved when the liquid waste from the oil works was re-routed into the town sewer, and production at the oil works was resumed. |

But the boom days were not to last. The year 1887 was the turning point, and from then on the company's financial situation deteriorated. A liquidator was appointed in September 1892, and the works were put up for sale in January 1893. Most of the employees were paid off shortly after, and the plant was put on a care and maintenance basis while attempts were made to put together a rescue package.

However, there was to be no rescue, and the works closed completely in 1894. The machinery was dismantled and sold immediately, although it was not until 1905 that the land was sold - first to the Whinnyhall Estate Company, and by them to the British Aluminium Company. But that's another story!

We'll leave the final word to William Erskine, writing in 1930: "Nature is doing its best to cover up the remains, and the winds moan their dirge through the rank grass. Overhead, the bings of refuse have become solidified into a squalid monument to man's aggressiveness in Nature's womb, and to his inability to find use for the matter that he has robbed of its virtue."

Webpage by Iain Sommerville;

Help

on bookmarking this page.